Harlots got the less salubrious side of London’s history a lot more right than you may think…

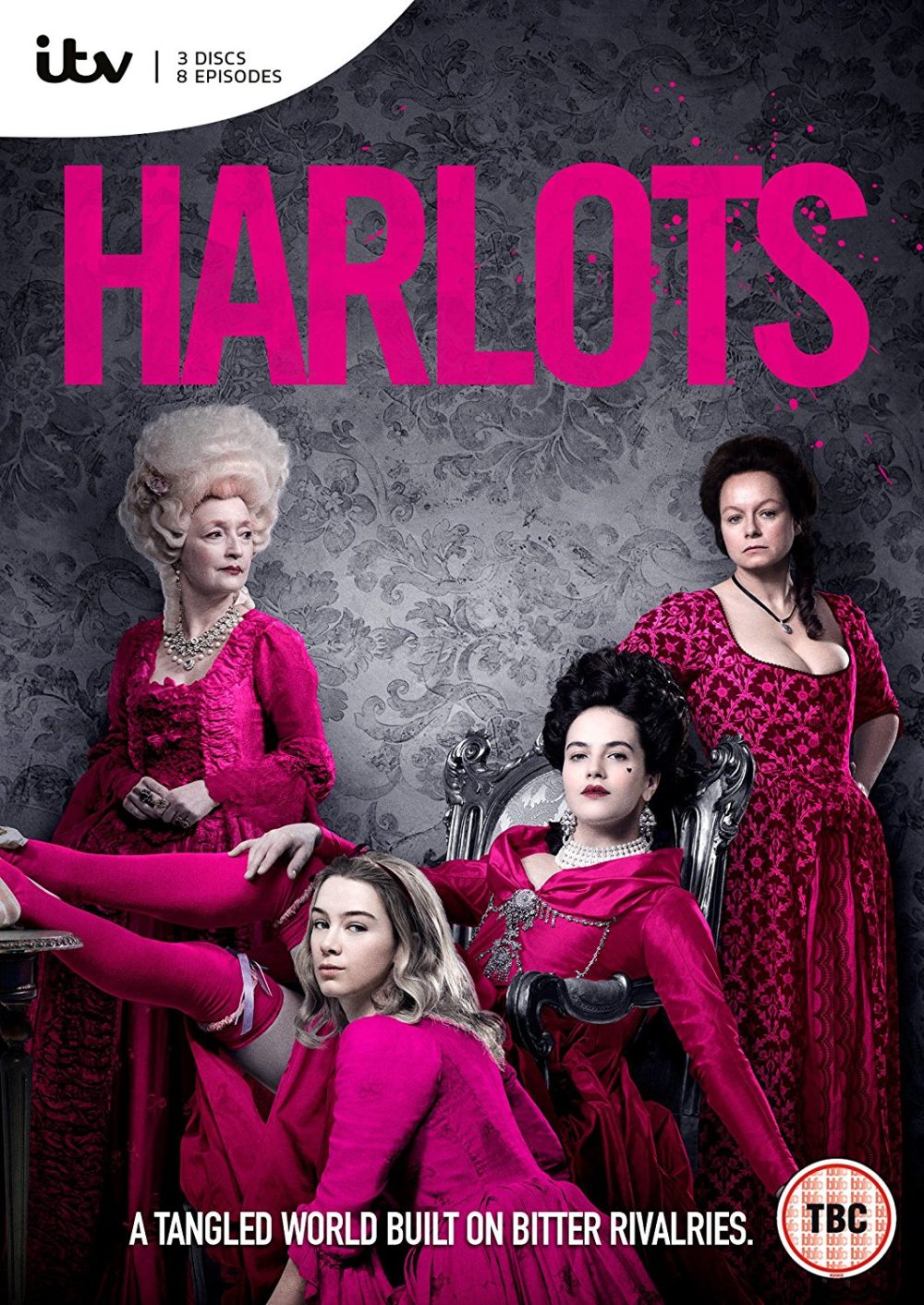

Set in 1763, Harlots tells the tale of two Madams at war. Their bitter rivalry, and competition over the spoils generated by upper-class customers of London’s thriving Soho, is the thread holds the series together. During the course of the show’s eight episodes, we see the lengths they which they will go to get to each other, and the effect their clash has on those closest to them.

Margaret Wells (Samantha Morton) has a brothel is in a down-trodden area of the capital, but she’s making her move upwards, aiming to move her family and her girls and take a new house in a vibrant new area. She is determined to take her piece of the wealth of this great city and is hungry for success. However, Lydia Quigley – owner of one of the most fashionable, successful, and unhappy brothels in Soho – has other ideas.

To coincide with the DVD release of the series on June 5th, we thought we’d take a look back at five times the fiction of Harlots got the truth of Georgian London absolutely right.

Prostitution in London

Prostitution in London

The premise of warring Madams may seem lascivious, but Georgian London was rife with such activities and they played an important part in the city’s economic history.

Jessica Brown-Findlay’s research for her role as Charlotte Wells led her to believe that “One in five women in London was involved in the sex industry at the time.” Many of those women were employed in and around the area of Convent Garden, exactly where Charlotte’s mother Margaret Wells (Samantha Morton) is trying to get her girls away from, if only to attract higher-class clientele.

According to the author Saunders Welsh – London was just, if not more, bawdy than Harlots portrays. For example, in 1758, he wrote:

“Prostitutes swarm in the streets of this metropolis to such a degree, and bawdy-houses are kept in such an open and public manner that a stranger would think the whole town was one general stew… like beasts in a market for public sale” and with language, dress and gesture too offensive to be mentioned.”

Prostitution as an economic option

Harlots centres around two businesswomen in fierce competition, and the lengths they’ll go to in their ongoing war.

The truth of the times in which Harlots is set, is that the sex trade was one of the few chances for women to financially better themselves in Georgian times. In his book, The Secret History of Georgian London: How the Wages of Sin Shaped the Capital, the historian Dan Cruickshank links the rise of prostitution in Georgian times to the economic development of the city. Specifically, to a construction boom that changed the look of London itself. He sees it as the product of an age that expected, even tacitly encouraged, men to pay for sex, while barring women from everything but the most menial industry.

Eventually, the kind of kick-back from puritanical campaigners that we see leveraged by Lydia in the series did have an effect. Cruickshank, however, appears to be far from convinced this was the sole reason for prostitution’s decline towards the end of the century. He also cites increased opportunities for women to work as another possible reason.

French Pox

French Pox

When, in episode two, Margaret finds one of her rivals’ girls dying of ‘French Pox’, she’s simply using one of the many, many names for Syphilis bandied around at the time. The prevalent one, as it happens.

A disease that first hit the medical books around 1500, its nicknames were often derogatory to an country’s enemy or another country thought responsible. Indeed, even the use of the word Syphilis itself is said to have been derived from from the cautionary poem Syphilis, sive morbus Gallicus’ (Syphilis, the French Disease) by Giralomo Fracastoro from 1530. The word didn’t work its way into British use until the mid-18th century, though.

Harlots’ setting in time coincides with the end of the Seven Year War. Though that took place in the American colonies, it had embroiled Great Britain and France’s armies. Thus, it’s not surprising Londoners were still using the more common term ‘French Pox’ and pinning it on their enemies across the channel.

Laudanum

Harris’ List

Yes, there really was an annual publication that listed and reviewed the prostitutes of London. Harris’ List – subtitled the ‘Man of Pleasure Kalendar‘ – was, in fact, published between 1757 and 1795, apparently selling around 8,000 copies a year.

It was far from the first of its kind, either; Wandering Whore was published as early as 1660, while the lavishly named A Catalogue of Jilts, Cracks & Prostitutes, Nightwalkers, Whores, She-friends, Kind Women and other of the Linnen-lifting Tribe was printed in 1691.

Harlots is available on DVD from June 5th, you can order it from Amazon here.