With 2017’s Doctor Who season well and truly underway, it won’t be long before Steven Moffat regenerates into new showrunner Chris Chibnall.

In anticipation, CultBox guest writer Ellie Mann has been looking back at Chibnall’s previous episodes to get some sense of what his tenure may bring…

Fantasy meets reality

As I try to make sense of the mostly nonsensical notes I’ve made as I’ve been re-watching Chibnall’s episodes, I notice one word crops up more than any other … ‘believable’.

It’s not a word you often hear people use in connection with Doctor Who, and it seems even less likely to crop up when discussing a selection of episodes that include the preposterously titled Dinosaurs on a Spaceship. Yet Chibnall’s stories do seem to have an element of realism that many other Who episodes lack.

In particular, it’s the threats faced by the characters that seem to be based in reality. Take Chibnall’s first episode 42 – ok, so the idea of a sentient sun reaping revenge on the humans who exploited it is a difficult one to swallow, but the real danger is that the sabotaged ship carrying said humans, is minutes away from destruction. We’re surrounded by machinery every day, we know how unreliable it can be – so it’s much easier for us to identify with a group of humans simply struggling with mechanics, than it is to sympathise with an alien intent on preventing solar fracking.

Dinosaurs on a Spaceship is the same but different. It’s another out of control spacecraft, this time, heading towards Earth. With no other information, the humans in charge of defending the planet can only assume that it’s a hostile threat and have no choice but to destroy it with missiles. I think that’s a legitimate reaction, and one I can believe NATO would make, were something similar to happen in real life.

Then there’s The Hungry Earth and Cold Blood in which the Silurians and humans came dangerously close to war. If there’s a sure-fire way to antagonise someone, pointing a massive drill at their civilisation is probably it, and since humans have been mining the Earth for thousands of years, it’s not too difficult an idea to comprehend. Setting these eps in a sleepy Welsh mining village is a great way to ground them in something recognisable.

True, Chibnall’s episodes haven’t given us anything to conceptually rival the likes of Blink or Heaven Sent so far, but he clearly knows how to write a solid story with a believable threat. If the latest series of Broadchurch is anything to go by, he also has a knack for writing with forensic detail. The opening episode which showed the police bagging and labelling every bit of evidence relating to Trish’s attack was sensitive but completely absorbing. Of course, Doctor Who is a very different show but it shouldn’t necessarily treat its viewers any differently.

The best Who episodes take the time to establish a believable world for the story to take place in, so I hope Chibnall takes his previous approach forward into the new era.

Tick, tock goes the clock…

There was another word that kept cropping up in my notes too … ‘countdown’. In fact, there was a countdown, of one form or another, in every one of Chibnall’s episodes. Some, it’s fair to say, don’t add an awful lot to the story – it remains a mystery as to why the minimalist paperweights in The Power of Three bothered to count down from 7 – The Shakri spent all that time waiting for people to take them into their homes and let their guards down, then effectively turned them into ominous egg timers so everyone panicked and got rid of them again. Clearly, the Shakri ain’t so sharp.

Some of his countdowns work incredibly well though. In Dinosaurs on a Spaceship, the Doctor has limited time to find out who the vessel belongs to and change its trajectory before the aforementioned missiles from Earth destroy it. In The Hungry Earth, The Doctor, Nasreen et al have 12 minutes to install sensors around the village before the Silurians burrow up to the surface. In Cold Blood, it’s “squeaky bum time” as the Doctor must get everyone out of the Silurian layer before the drill starts up again and their exit route gets obliterated.

A good countdown can really focus the action. They’ve been used countless times in Doctor Who, often with stunning results. There were the 82 minutes the Doctor conjured up between visits from the veil in Heaven Sent, in The Eleventh Hour he had twenty minutes to prevent the Atraxi incinerating the Earth. In Mummy on the Orient Express, we got an actual on screen timer, warning us that in 66 seconds, the Foretold would claim its next victim. When the story is heading towards an inevitable conclusion, a countdown can add both jeopardy and mystery. We might not know what’s coming, it may seem like the Doctor has no chance of stopping it in time – either way, as the seconds tick away, the tension rises.

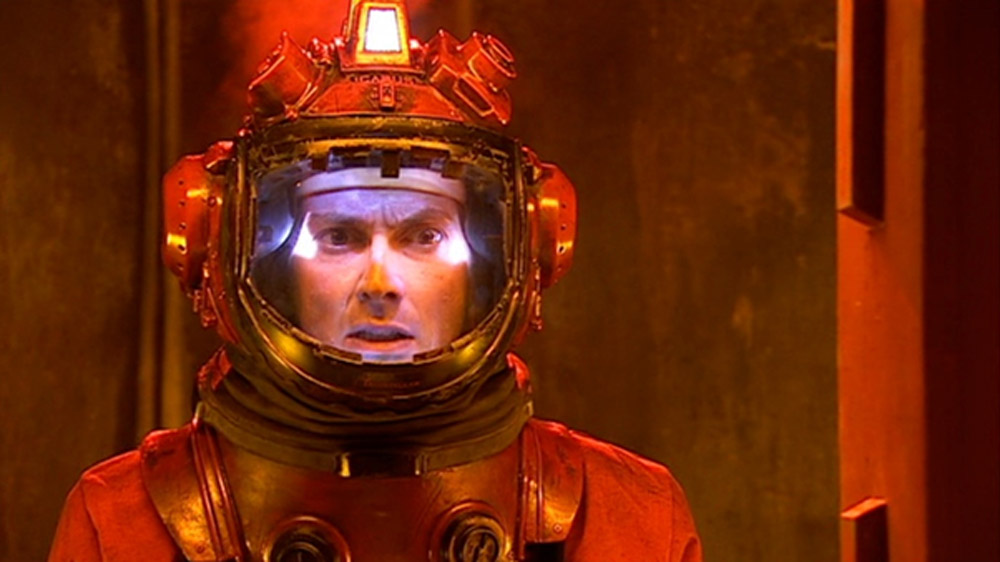

42, arguably Chibnall’s most memorable episode, is effectively one big countdown. Doctor Who’s only real-time episode to date, from the minute the Doctor and Martha arrived on McDonnel’s Cargo Ship, they were in play, as they battled to get the auxiliary engines up and running before the ship crashed into a nearby star.

The intensity didn’t let up for a second as the story cut between groups of characters in various parts of the ship simultaneously working to repair it and save themselves. Standing between the crew and the engines were a series of password protected doors, yet another obstacle to overcome in an inconceivably short amount of time and the resultant episode was nail-biting, claustrophobic and highly original.

If Chibnall can inject the same kind of pace into the new era as he’s managed in his previous eps, we could be on to a good thing. And I think it’s about time we had another real-time episode, don’t you?

The human touch

If there’s another thing that shines out in Chibnall’s writing, it’s his characters. I’d go so far as to say that every one of his episodes has had a strong ensemble cast. Dinosaurs on a Spaceship loses points for the sheer randomness of Nefertiti and Riddell the big game hunter, but introducing Rory’s Dad was a masterstroke. The dynamic between Brian, Rory and the Doctor was a comic delight, and Brian himself was compassionate, philosophical and not afraid to ask the really big questions such as “Is that a kestrel?” and “What sort of man doesn’t carry a trowel?” (Rory, in case you were wondering).

42’s full of great character moments too. The whole section between Martha and Riley as they’re stuck in the jettisoned capsule is, to use that word again, believable. They’re adrift in space, cut off from everyone else, completely helpless and completely alone and Martha is very aware of the impact her disappearance will have on her family. They’ll never know what happened to her, never find her body, they’d always be waiting for her to come home – it’s a sobering thought and Martha’s tearful phone call to her mother is full of poignancy.

Chibnall seems aware of his characters, always striving to give them extra details to make them more real. Take Rory for example, we learn that he’s a nurse in his very first episode, but after that his medial skills are barely mentioned, except under Chibnall’s writing. Tiny things like him checking to make sure no one was hurt in the church in The Hungry Earth, performing first aid on his Dad in Dinosaurs on a Spaceship and rushing to help out at the hospital when the cubes started injuring people in The Power of Three, gave Rory so much more depth and purpose.

What’s most exciting, for me anyway, is Chibnall’s awareness of the Doctor’s character. You’d think that after 54 years, every facet would have been explored, but Chibnall manages to find subtleties in the Doctor that make him more complex and ironically, more human. There’s a moment between Amy and The Doctor in The Power of Three, after they’ve been to the Tower of London, where he expresses his regret at not making sure the cubes were collected and burnt earlier. It’s one line but it’s an admission that he dwells on his mistakes and an acknowledgement that he doesn’t always consider the consequences.

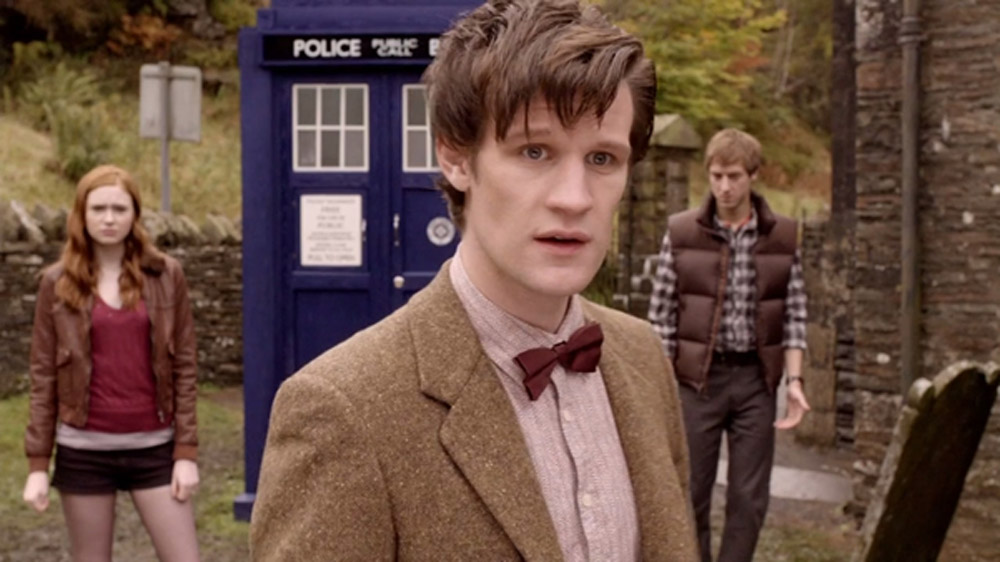

In The Hungry Earth, it’s partly the Doctor’s fault that Elliot gets taken after he lets him leave the church unaccompanied. You can see the look of shame on Matt Smith’s face as The Doctor realises his negligence. In Dinosaurs on a Spaceship, he’s quite different – the man who never carries a weapon and abhors violence, despatches Solomon quite ruthlessly, his mercy all used up.

So, though Chibnall’s episodes have often been overshadowed by flashier, more fantastical affairs – they’ve shown that he is a writer who delivers good solid stories and good solid characters. His simplistic approach, coupled with a new writing team full of fresh ideas, could be just what the show needs in its next phase and, after the high-profile spoilers that have accompanied this series, I’m intrigued to see if Chibnall will use his well-honed secret keeping skills to bring a sense of intrigue back to proceedings.

He’s proven with Broadchurch that he can helm a flagship show under intense scrutiny so I’ve got every faith that Doctor Who’s in safe hands.

What are your hopes for Chris Chibnall’s era? Let us know below…