Doctor Who, the show that can go anywhere and do anything. It’s vital, it’s delightful, it reaffirms your faith in humanity, with a hero who is never cruel or cowardly.

And yet…

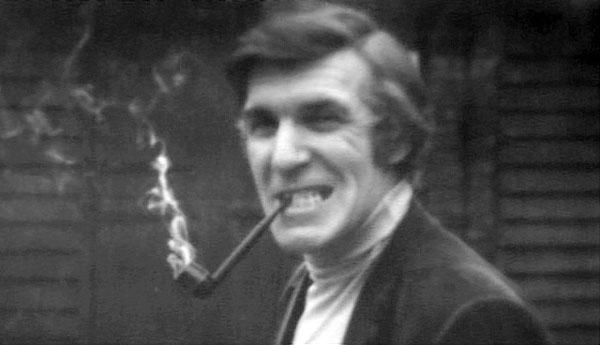

Robert Holmes is widely regarded as the best writer/script editor of Doctor Who, either ever or at least from its first 26 series. His writing was cynical, violent, blackly comic, and frequently makes more sense if read as an attack on or parody of Doctor Who itself. The most moving scene he wrote was not about affirming humanity, but about giving someone the knowledge that the belief they were tortured for was true all along.

So, his writing jars with the public perception of Doctor Who – or at least, the public perception of Doctor Who now, but Russell T. Davies called Holmes’ dialogue for The Talongs of Weng Chiang ‘the best dialogue ever written. It’s up there with Dennis Potter.’

This is one of the reasons people like him. Ripe, quotable dialogue. He was also fortunate to inherit the lead actor pairing of Tom Baker and Elisabeth Sladen, with Ian Marter on board for Season 12. With the previous producer, script editor and lead actor leaving the series at the same time, Holmes was fortunate enough to learn from his time writing for them but to be given a cleaner slate to work with.

UNIT were already being phased out, and the Doctor would be spending more time in space than on Earth. A new Doctor and a new producer, both of whom Holmes had good relationships with, allowed him the opportunity to develop things in tandem with them. Their initial success gave them momentum.

Indeed, Tom Baker’s Doctor took the edge off some of Holmes’ ripe dialogue. While the Doctor harangues Marter’s Harry Sullivan in The Ark in Space – and you can imagine Pertwee’s Doctor doing something similar – Baker’s eyes are starting to twinkle. There’s a distance between the Doctor and Harry that makes him seem alien rather than domineering. Plus, Holmes gives the Doctor his ‘Indomitable’ speech about the human race.

This is not merely dialogue that would need tweaked for the Third Doctor, it’s a sentiment it’s hard to imagine him expressing in such depth.

It is also hard to imagine the Third Doctor in a story which is essentially Alien for children.

This story, The Ark in Space, was a rewrite of a rewrite. Originally pitched in late 1973 by Christopher Langley, the original scripts proved unsatisfactory. John Lucarotti was brought on board to write new scripts based on the concept. Holmes had never liked the six part Pertwee stories, and so sought to turn them into a four parter and two parter made by the same production team – saving money and reducing the need for padding. As a further cost-saving measure the space station would be used in another story.

Then Lucarotti’s scripts were deemed unusable. Holmes had to write the story from scratch.

This quality control threshold is reminiscent of Derrick Sherwin. However, now that Doctor Who seasons were shorter than the late Sixties, Holmes was able to maintain a higher standard of stories, or at least make sure the lesser ones didn’t drag on for another two episodes.

Hinchcliffe and Holmes honed the production template they’d inherited, building on the work of their predecessors. As with many production teams, they wanted to aim the show at an older audience. They managed to do this for longer than most, before the outcry from Mary Whitehouse persuaded the BBC to move Hinchcliffe onto a more adult-orientated series.

The influences that pushed Doctor Who in this direction were gothic horror novels and their movie adaptations (e.g. Frankenstein, Jekyll and Hyde) but also classic Science Fiction movies. Quatermass (again) and The Forbidden Planet were other sources of inspiration, often merged with the previous gothic influences. Bringing in new writers, some of whom hadn’t seen Doctor Who, meant they defaulted to something closer to The Avengers.

Essentially, Holmes was always happy to pilfer old stories and styles, then work them into Doctor Who‘s format. It was the storytelling equivalent of grave robbing – digging up old stories in order to rummage around in their innards, and learn things about how they worked.

Like their predecessors, Hinchcliffe and Holmes wanted to move on after three series, and had developed their own series as a way out. However, due to the outcry over The Deadly Assassin – drawing an apology from the Director General of the BBC – Hinchcliffe swapped jobs with Graham Williams at the end of Season 14 while Holmes stayed on for a few stories to help with the changeover.

There are several legacies Holmes left Doctor Who with. He and Hinchcliffe successfully reworked Doctor Who for an older audience. The format of travelling through time and space having adventures had now been re-adopted, blended with classic stories and memorable characters.

Holmes was incredibly good at suggesting more with a few lines, creating a rich pantheon of villains, henchpeople and supporting characters. The production team consulted with designers, directors and special effects teams to see what was possible on their budget and wrote accordingly. The scripts were generally good, and when they weren’t the leads were always watchable. Viewing figures increased further.

However, after Hinchcliffe learned that he was being moved on from the show, he loosened the purse strings for his final story. This led to Graham Williams moving into the show under strict instructions to tone down the violence, up the humour, and work on an even lower budget than usual.

Hinchcliffe and Holmes had, through both quality and chutzpah, made Doctor Who in such a way that whoever followed them would have a hell of a task on their hands. Knowing that the BBC were imposing edicts on the show, Holmes’ scripts grew more viciously satirical, becoming increasingly abrasive.

Yet it was this nerve, this ability to laugh bitterly at the seriousness of it all, that is one of Holmes’ most appealing qualities to his fans. My favourite gag of his that never made it to the screen was his idea to finish the credits of The Deadly Assassin Part Four with the following caption:

“We thank the High Court of Time Lords and the Keeper of the Records for their help and co-operation”.

Really, you’ve got to admire the nerve of the man.